Childcare program participation drops

2023 summary report for the Early Childhood Program Participation survey

The first look report at the 2023 Early Childhood Program Participation survey came out this week! I have been checking for it about once a week since August, and I’m so glad it’s finally here, even if I’m still waiting for the full data files.

The big takeaway is that regular, weekly non-parental childcare arrangements dropped. It had held pretty steady for all children under six and not yet in kindergarten since the earliest data collection in 2012 until 2019, but then dropped four percentage points in 2023.

Childcare arrangement by age doesn’t seem to have significantly changed for infants, but it dropped from 55% (±1.2) to 50% (±1.3) for children aged one and two and from 74% (±1.2) to 67% (±1.3) for children aged three to five. For family structure, it dropped a bit for kids living with both parents — 58% (±0.9) to 55% (±0.8) — and much more for kids living with one parent or guardian: 65% (±2.1) to 54% (±2.3).

While program participation dropped for children across all income levels, there was a larger change for the poorest children (families making less than $20,000 a year), whose program participation dropped by a third from 51% (±2.6) to 34% (±2.7), compared to a 9% drop for children in families making more than $100,000 per year — 74% (±1) to 68% (±0.9).

A corollary to that is the large increase in hourly out-of-pocket childcare costs. Most children aren’t in a fee-based childcare arrangement. Many don’t have any non-parental care arrangement, and then some are in free public childcare (like school-based pre-K programs) or are cared for by relatives who don’t charge the parents. But the hourly cost of center-based childcare jumped from $9.80 (±0.31) in 2019 (adjusted to 2023 dollars) to $21.32 (±0.51). This could be a composition effect, if children in lower cost childcare arrangements either left or the programs closed, leaving behind children who were already in costly centers to remain in the sample, or center fees may have really doubled after inflation since 2019. Infant center-based care went from $9.43 per hour to $25.29 per hour.

The hourly cost of relative care also increased, but not as starkly. Just under 5% of children were cared for by a paid relative in 2019 at the average cost of $7.21 per hour across all surveyed age groups. That jumped to $10.94 in 2023.

I was curious whether the jump in childcare costs affected all incomes and parental education levels similarly. Parents with a high school diploma paid an average of $8.58 (±2.38) per hour of center-based care in 2019, while parents with graduate degrees1 paid $11.36 (±0.51). In 2023, that jumped to $10.22 (±1.39) for parents with a high school diploma — or within the margin of error from 2019 — while for parents with graduate degrees it increased to $25.32 (±0.68). For income, households making between $20,000 and $50,000 paid $7.59 (±0.86) per hour in 2019 and $10.19 (±1.3) in 2023, a 34% increase. Households making over $100,000 paid $10.92 (±0.36) in 2019 and $24.39 (±0.59) in 2023, a 123% increase. For whatever reason — sample composition, willingness or desire to pay for higher cost programs, or comparatively steeper increases in top-cost-tier childcare — higher income parents had higher increases in out-of-pocket costs.

Another shift that surprised me was how parents valued indicators of quality. Child care quality is a tricky research subject. Chris Herbst and Jessica Brown have done really interesting research on the impact of wage increases on staff turnover, staff quality, teacher-child ratios, and parental satisfaction and (surprisingly to me) showed that parent satisfaction dropped even as positive quality indicators increased. High quality child care is expensive, and older federal research indicates that a lot of US formal child care options are mediocre-to-poor. Longitudinal research on high quality programs like Tulsa Educare indicates positive long-term outcomes — plus hopefully the children enjoy it more — while other natural experiments from Quebec and Tennessee indicate that when kids move out of an otherwise higher quality care environment into a lower or mixed quality environment, there can be negative long-term effects. Lots of people disagree about the exact effect sizes or causes or how to measure quality, but in my opinion it’s fairly intuitive that things like teacher pay, teacher qualifications, and how many small children a single adult is expected to care for affect the sort of care little kids are getting.

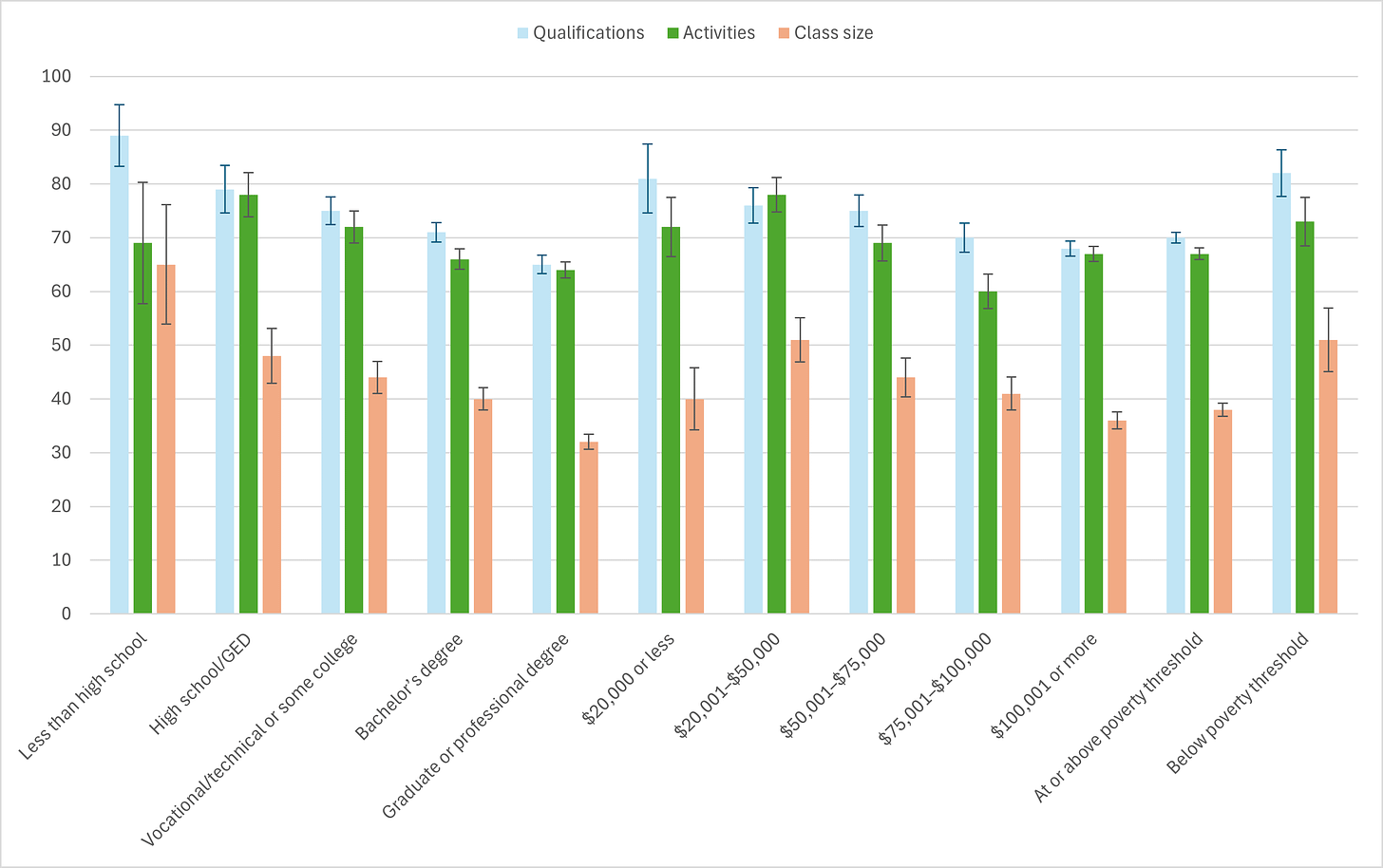

So I was surprised to see that higher educated and higher income parents — a group that frequently receives media focus for “intensive parenting” — reported valuing teacher qualifications, learning activities, and class size less than less educated and lower income parents. I would have expected that the parents who had the most resources to put towards child care would value these care aspects the same, or possibly even higher, than parents with fewer resources.

79% of parents (±4.4) with high school diplomas rated staff qualifications as “very important” for choosing childcare, whereas the same question was 71% (±1.8) for parents with bachelor’s degrees and 65% (±1.7) for parents with graduate degrees. Likewise for income, 81% (±6.4) of parents making less than $20,000 a year and 76% (±3.3) of those making between $20,000 and $50,000 rated teacher qualifications as very important, compared to 68% (±1.4) for those making over $100,000. Parents living below the poverty line rated it as very important 82% of the time (±4.3), compared to 70% (±) for those above the poverty line. Learning activities and number of children in care group followed similar patterns.

When it came to reliability and religious content, there weren’t large income or education differences. Parents with more income or education did report valuing cost less highly than other parents, but that wasn’t as surprising to me.

Do higher income/higher education parents value other care aspects that aren’t captured in this survey? Are they less concerned about child care quality than parents with fewer resources? Are they less likely to report valuing indicators of quality? I’m not sure, and the data available in this survey can’t provide answers. One hypothesis I have on the learning activity question is that higher income/education parents may value “play-based” early care and see that as opposed to learning activities. Dale Farran,2 an early childhood researcher at Vanderbilt, talks about a shift to play based early education among middle-class children and how providing that in public pre-kindergarten programs may be more important than more “academic” settings that resemble first or second grade classrooms. But I really have no idea when it comes to qualifications or class size.

When it came to looking for care, not all parents looked and some looked and didn’t find care. Again, this varies by income and education. Parents reported having “some” or “a lot” of difficulty finding care at similar rates across income and education groups. But 55% (±0.9) higher income ($100,000+ household income) parents reported looking for care compared to 37% of parents making less than $20,000 (±3), between $20,000 and 50,000 (±1.8), and $50,000 and 75,000 (±1.7). 61% (±1.1) of parents with graduate degrees looked for care compared to 31% (±2) of parents with high school diplomas.

While parents who found care reported similar levels of difficulty, lower income and less educated parents were more likely to say they just didn’t find a child care arrangement. 5% (±0.8) of parents with graduate degrees reported not finding child care, compared to 10% (±1.1) of parents with bachelor’s degrees and 17% (±3.2) of parents with high school diplomas. Only 5% (±0.6) of parents making more than $100,000 as a household reported not finding a care arrangement.

And that’s it for the summary report! I’m looking forward to the full data files.

Once the data files come out, I’ll be able to do wider educational groupings that encompass all parents with college degrees or all parents with high school diplomas

Who was also surprised by her research results, and it’s interesting to listen to her talk about what she was expecting and how her research has shaped her current thinking

Interesting! As a more educated etc parent I think natural warmth and affection for infants and toddlers is orders of magnitude more important than any certificates. Kids can tell if caregivers care about them and other than literal maiming or death that is way more important than anything else in positive outcomes for kids. Though if there are too many kids to be able to supervise them or be able to pick crying ones up that’s obviously an issue.