Almost two years ago, Matt Bruenig of People’s Policy Project had an opinion piece in the New York Times on Nordic-style home child care allowances. It was a good article, and I also enjoyed his follow-up refuting some opposition views. If you’re not familiar with home (or parental)1 child care allowances, I highly recommend reading through both of his articles first.

But what has stuck with me two years later in my adventures through time use data is this paragraph:

One also has to wonder how exactly Filipovic’s alternative to home care, which is child care services, is any different in this regard. The child care sector is almost entirely staffed by women, disproportionately women of color and immigrants with low levels of education. What does this “reinforce” in our culture? That child care is properly done by the lower class women of society?2 How inspiring.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 94% of child care workers (median wage $13.71/hour in 2022) and 97% of preschool and kindergarten teachers ($16.99/hour) are women. In Norway, it’s 82% and 90% respectively. According to American Time Use Survey Data from 2003-2022,3 women reported 99.8% of the working hours of paid child caregivers. Using ATUS data, I was able to build a model of how child care time would be allocated under two scenarios: a two parent family with at least one child under 6 where mom is out of the labor force and dad is employed and a two parent family with at least one child under 6 where mom is employed for 40 hours per week and dad is also employed.

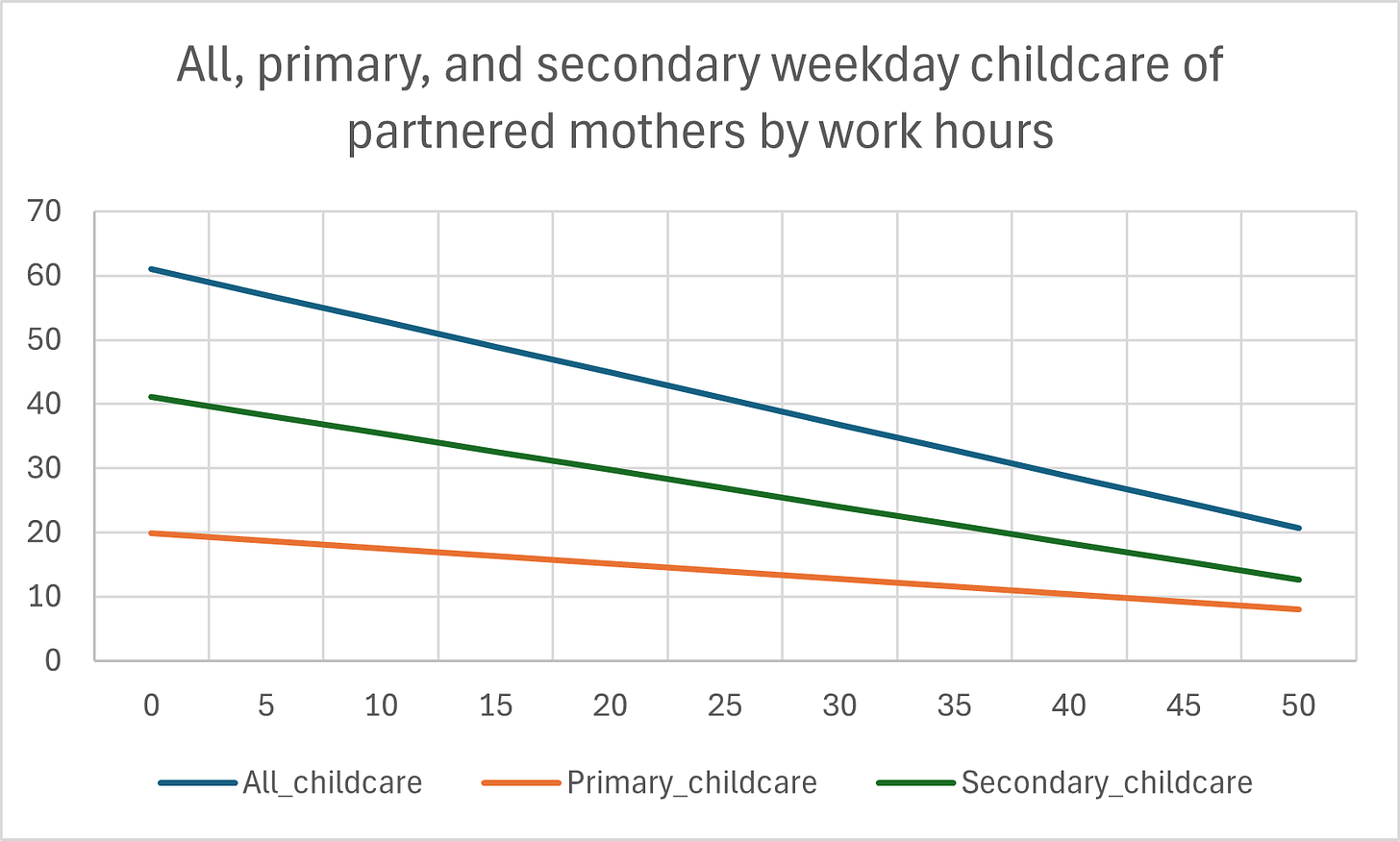

Under the first scenario, mom reports 62 weekday (Monday through Friday) hours of combined primary and secondary childcare and dad reports 20.8, giving them a 75%/25% split. Under the second scenario, mom reports 28.2 hours of childcare and dad reports 22.9, giving them a 56%/44% split. But this is not the only childcare being done in many scenarios, because children under 6 can’t be left alone. The parents are likely relying on a non-parental care arrangement, whether that’s a paid or unpaid relative or a paid child care worker. So the second scenario is actually 28.2 hours of childcare for mom, 22.9 hours for dad, 39.9 hours for a female child care worker, and 0.1 hours for a male child care worker. In short, a 75%/25% split between women and men. The linear models for all (primary+secondary), primary, and secondary weekday childcare hours by reported weekday work hours are shown below.4

This model has some limitations. The parents could be staggering their work hours to reduce non-parental care time and costs, or they could have commutes that push market child care usage higher than 40 hours. According to the 2019 survey of Early Childhood Program Participation, 20% of two-parent families where both parents were in the labor force had no regular non-parental childcare arrangement. That number drops to 13% when both parents are employed full time (19% when the mother is employed full time does not have a college degree versus 10% when she has a college degree).

Families with a stay-at-home-mom could be using additional non-parental childcare which, if it decreased fathers’ childcare time, would be increasing the caregiving share done by women. However, in general we can see that while shifting care work from non-market to market moves intra-household child care time closer to even, it does nothing to reduce the amount of time that women overall spend providing child care.

Filipovic wrote:

Creating incentives for mothers to stay home, even if those incentives are gender-neutral on their face, reinforces the idea that women are and should be the primary caretakers of children, and that affects everyone — not just the women who choose to stay home.

As Bruenig points out, there’s little evidence to suggest that home child care allowances affect childcare decisions, and as time use data shows, moving childcare work from non-market to market also doesn’t do much to change how much child care is done by women.

Sometimes home child care can be used to refer to in-home daycares, which go by a variety of names

There’s an interesting paper that found increased immigration was linked with increased employment hours of “high-skilled native women,” because it was easier to substitute household production in the market a.k.a hire a housecleaner or nanny: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31234/w31234.pdf

Except 2020, because of an issue with experimental weighting comparability

R-squared values: all, 0.51; primary, 0.16; secondary, 0.34