Valuing Informal Care in the Nordic Countries

Even in high-program participation countries, parent-provided care substitutes for expenditures and women do most of the work

The Nordic countries spend a lot of money on child care. In return, they have high maternal labor force participation and child care with structural markers of quality — things like (generally) low child-to-adult ratios and (relatively) higher caregiver wages.1

American media may talk a lot about the benefits of high-quality child care, but how to provide high-quality child care, especially if quickly increasing the child care supply either through subsidization, direct provision, or a combination, gets less press. Vermont had a plan to expand access through subsidization and contribute to quality improvements through raising caregiver wages. The report estimated it would raise the cost of infant care to between $35,000 and $40,000 per child, which would then be offset by state subsidies to low-and-middle-income parents.

Surprise, surprise — the subsidies passed, the wage improvements didn’t. That’s not completely without precedent; some Nordic countries don’t have a minimum wage and instead set wages through sector-wide collective bargaining agreements. But the United States (or Vermont) doesn’t have sector-wide child care unions, so a minimum wage scale would be most direct way to influence the pay portion of child care quality.2

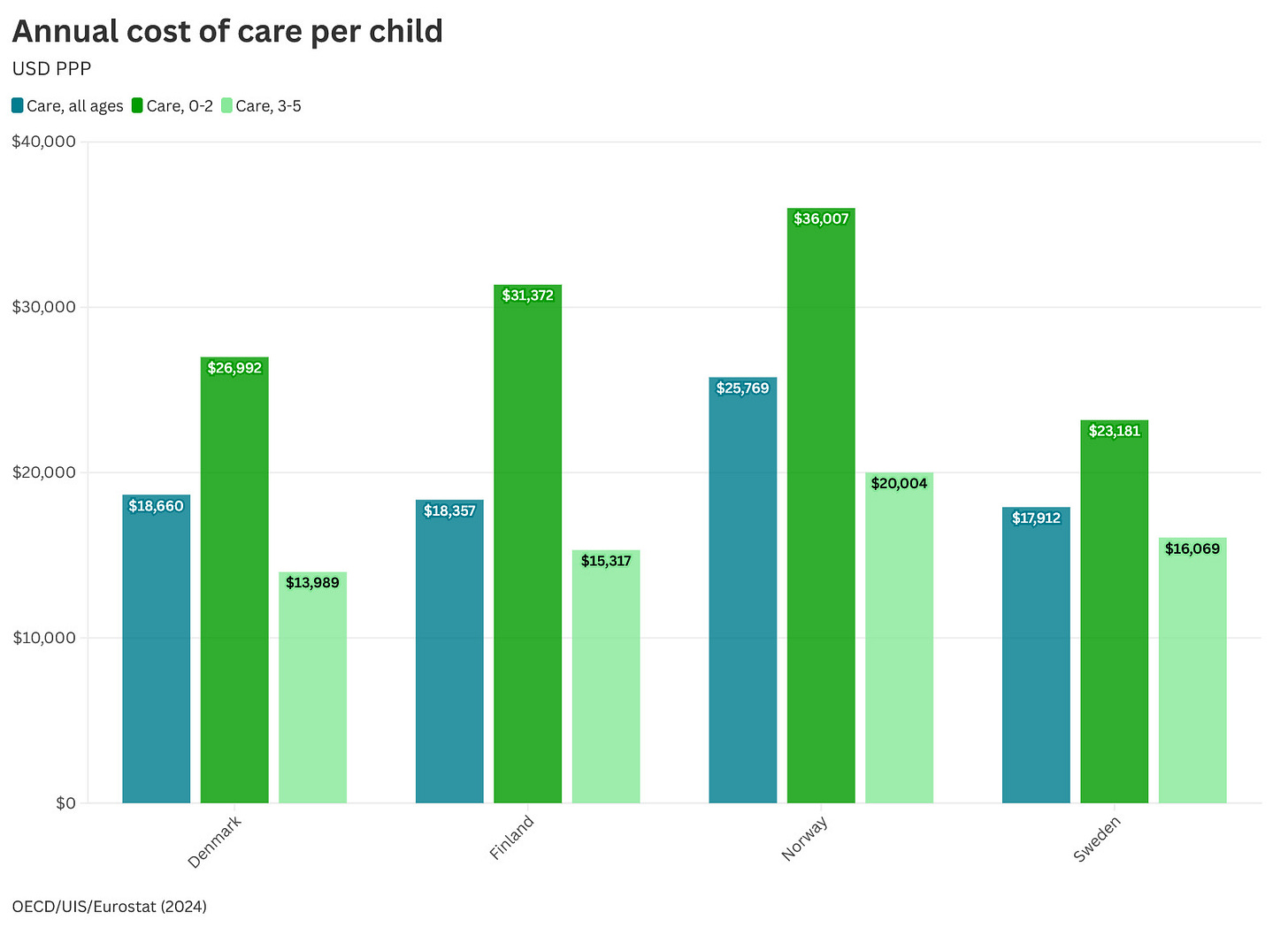

In Norway, one adult caregiver can care for up to three children ages 0-2 or six children ages 3 to 5. In Finland, its 4 children and 7 children respectively.3 In Maryland, meanwhile, 1 adult can care for 3 children ages 0-1 but six 2-year-olds.4 For 3- and 4-year-olds, it’s 10 kids per adult. For 5-year-olds, it’s 15. Nordic child care is expensive because they pay their caregivers better and because they ask them to care for fewer kids. The cost is spread over a lifetime and shared by non-parents via welfare policy, rather than front-loading it for ages 0-5 and placing the cost almost entirely on parents, but it’s not cheap child care.

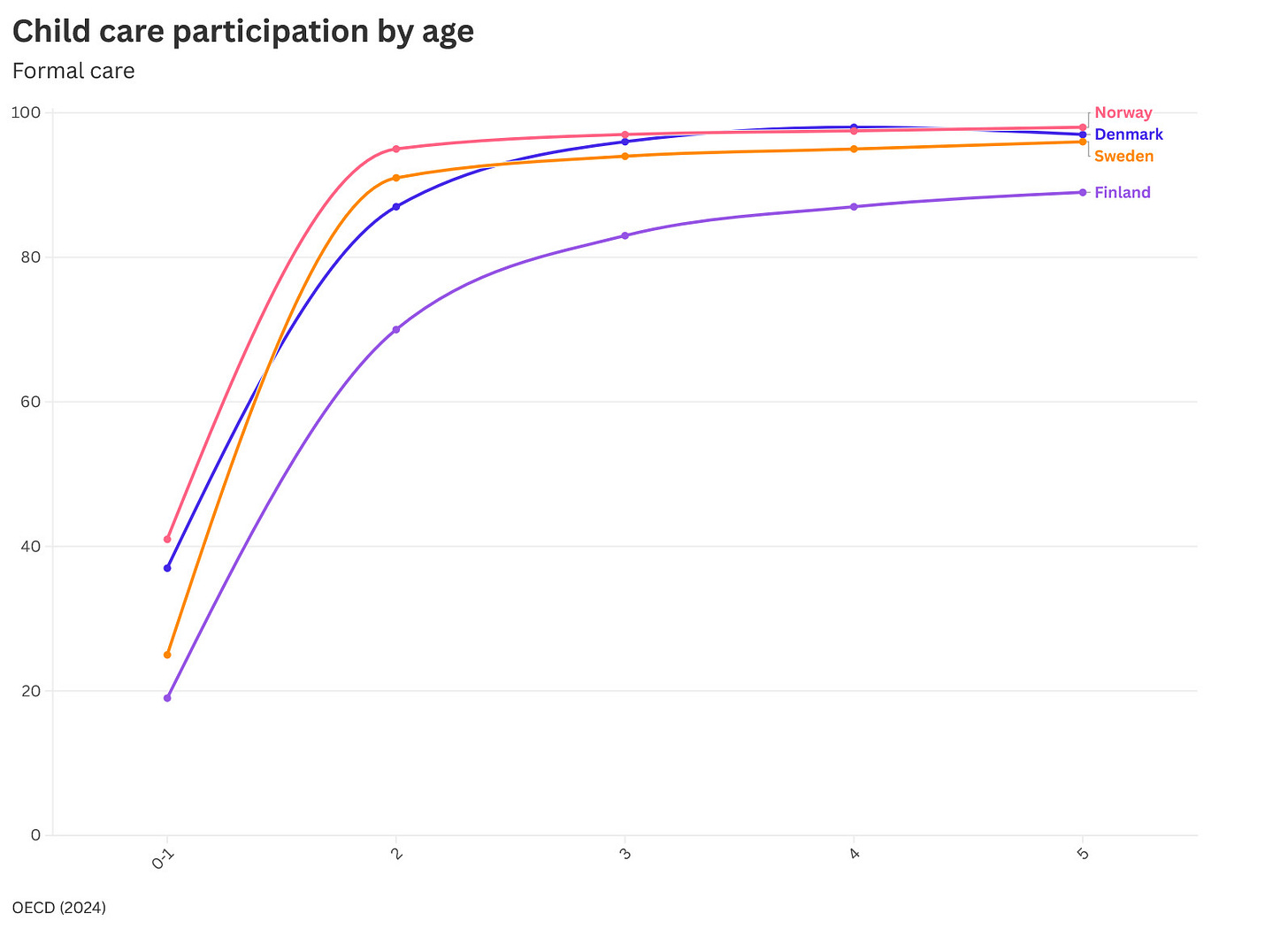

And while Nordic countries had generally high participation in child care, it wasn’t universal, especially in Finland and for children under the age of three. Mirroring the United States, no Nordic country had more than half of their infants and 1-year-olds enrolled in formal child care.

Which brings us to home production, or specifically the non-market provision of child care. Not counted in GDP, it’s nevertheless a large source of working-hours child care around the world. It’s commonly known as “stay-at-home moms,” though some dads also “stay home” and plenty of primary-caregiving parents still have some form of employment. Depending on how you measure it, it can also include unpaid relatives.

So what is this worth in the Nordics? What is it worth in the United States?

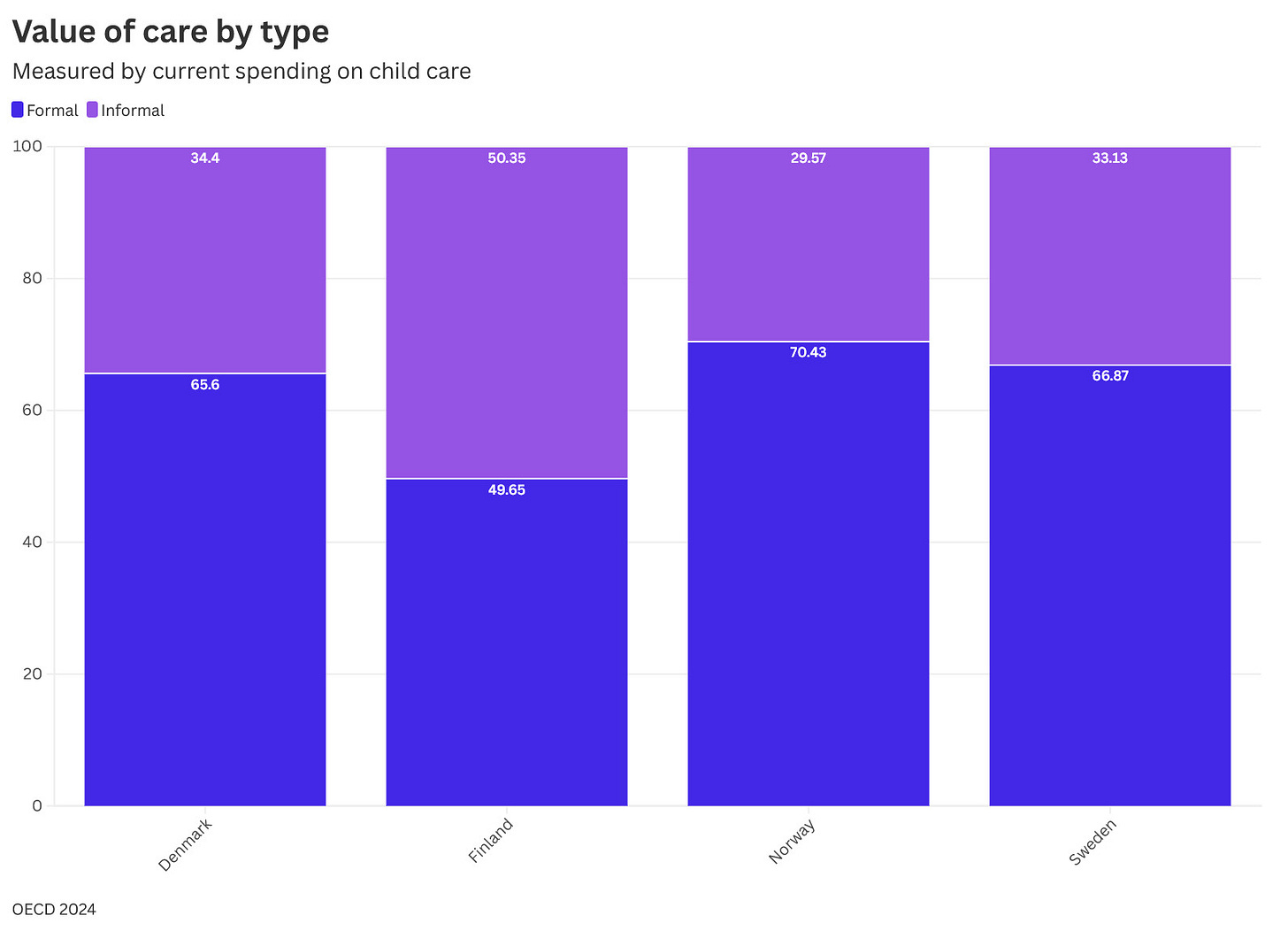

Non-market care as a function of current child care spending

One way to calculate the value is to look at the cost per child of providing formal care and multiply it by the number of children not currently receiving formal care. That’s fairly straightforward — look at the first graph.

In Finland, informal caregivers provided about half the total value of care, based on the costs if all those children entered the formal child care system. In Norway, it was about 30%.

I also looked at the per-caregiver value. This requires some estimation — I could have looked at the total value and divided by the number of parents out of the labor force, but that might not capture parents who are employed and not using child care. It also might not capture parents on parental leave. So instead, I assumed that each non-market caregiver was taking care of about the average number of children per family. That ranged from 1.41 (Norway) to 1.84 (Finland).

In Finland, a caregiver taking care of 1.84 children saved the overall child care system about $52,000 per year. In Sweden, a caregiver taking care of 1.43 children saved everyone about $32,000.

An interesting part of the Nordic child care market is how much better they pay their child care workers. In the United States, child care workers and preschool teachers earn a little over half the median wage. In Norway, they earned close to the median: 94%. In Finland and Sweden, it was 84%. This despite the fact that the child care workforce in all the listed countries are heavily female dominated — over 90% of child care workers are women in both the Nordic countries and the United States.

Who Cares for Children? (For Pay)

Child care workers are overwhelmingly women, poorly paid relative to the average worker, and more likely to live in poverty.

A note on parental care financial support

The Nordic countries already have some financial support for parental care — parental leave. Some also have a cash-for-care benefit.5 Both of these provide some amount of financial support for parents currently not in employment and caring for young children. But in the case of cash for care benefits, the maximum benefit in e.g. Finland is well under what the government pays for child care — maxing out at about $5,701 per year for one child. Parental leave also pays a portion of annual wages after a minimum. Even with less-scalable costs like buildings and administration, kids cared for at home are less expensive to the country than kids enrolled in child care.

Non-market care as a function of foregone wages

Another way to calculate the value is to look at how much the caregiver would have otherwise earned if they entered the labor market and enrolled their child in daycare.

Earning power varies by a wide variety of factors, including education and prior job experience. I decided to use 10th percentile wages because most caregivers entering the job market could probably earn that much. Many would earn even more.

With this method, the “cost” each caregiver is paying per child in foregone wages ranges from a low of $21,000 in Finland to a high of $38,000 in Norway.

The United States

Coming back home, what would it look like for the United States to implement Nordic-style child care? For under-3s, that looks like an average of about $29,400 per child, in line with Vermont’s estimates.6 For 3-5s, it’s about $16,300 per child.7 In the current United States funding model, most of that cost would be borne by parents, so it’s probably a non-starter — even at the (comparatively) cheap child care costs the United States currently has due to low wages, most families don't purchase child care.

If the United States wanted to implement Nordic-style child care, it would also have to significantly scale up its child care workforce. Sweden has 1 child care worker for every 4.5 children not yet in formal school and 1 child care worker for every 3.3 children enrolled in childcare. Norway (2.65, 2.09) and Finland (3.49, 2.31) are even lower. In comparison, the United States has 1 child care worker per 21.6 children and and 1 child care worker per 7.8 children enrolled.

As shown in the graph above, the United States has fewer working-age people devoted to caring for children than every Nordic country except Denmark.8 And this might even be an overestimate of unpaid caregivers because I just divided the number of children in parental or relative care by the average family size (1.94), but parents are more likely to stay home with higher numbers of children. But where it’s a real outlier is in paid caregiving.

While the Nordic model smooths out the cost of child care across the population via the welfare state, it doesn’t decrease the person-hours intensity of caring for children, and it still has the vast majority of that work done by women, even when it’s paid. Nordic women, as a population, are actually spending more of their “work” time on caring for children than American women. If the idea is to free up people (women) from child care to do other employment tasks, the Nordic model doesn’t accomplish that — but it does provide reasonably high-quality child care at a minimal cost to the end user.

Sources

Norway: Statistics Norway

Sweden: Statistics Sweden

Finland: Statistics Finland

Denmark: Statistics Denmark

OECD: Education at a Glance 2024

For more about the link between wages and child care quality, I suggest Jessica Brown’s paper Minimum Wage, Worker Quality, and Consumer Well-Being: Evidence from the Child Care Market

It would also draw more people into the profession, alleviating space shortages due to staffing, an issue Canada is currently dealing with

Though when it comes to 0-2 care, both countries have tiny rates of infant child care participation because of generous parental leave.

One legislator in Maryland wants to raise that to four infants per caregiver or five 1-year-olds per caregiver. Whenever I see proposals like that I always want to suggest anyone voting for it go care for four infants for a week and report back.

Insert disclaimers about comparing between currencies here.

Where publicly funded childcare for 3-5s does exist in the United States, it costs about $13,600 per child, according to OECD data

Denmark uses a different occupational coding system than Sweden, Finland, and Norway, so it’s certainly possible I’m missing a group though I did read through the whole section

Such an interesting collection of data, thank you! I’m an American and have lived in Norway for 11 years. I currently have two kids, ages 1 and 6, in “barnehage,” the universal daycare/preschool.

A couple of comments (about Norway specifically):

1. the reason that “no Nordic country had more than half of their infants and 1 year-olds enrolled in formal care” is because of paid parental leave. In Norway we have the option of taking 61 weeks of combined paid leave, with both parents earning 80% of their income (which is paid by the government) or 49 weeks of leave at 100% of your normal pay. I should also note that in Norway, paternity leave is “use it or lose it” as a way to force men to take their allotted portion. Here every child has a right to a “barnehage” spot starting from August in the year they turn one, but they must turn one by November of that year. Meaning that the vast majority of children aren’t starting barnehage until they are close to one. In our case, both our daughters were born in early spring, meaning that by the time my leave and then my husband’s was over (we took the 80%/61 weeks option), we had a short gap between when paternity leave ended in May and barnehage started in August. Both of my kids therefore didn’t start formal care until they were nearly 1.5 years old because of our long paid parental leaves and the time of year they were born.

2. During this gap period both times I stayed home; the first time I was laid off at that time from the pandemic and the second time I took unpaid leave. Both times I qualified for the “cash for care” monthly payment, which works out to about $700 a month with the current exchange rate. This option is often used for a short period of time, in situations like mine where a parent must stay home and is therefore losing income. In other cases families use the money to pay a nanny until barnehage starts. This option is only available from when the child is 13-19 months. Part of the reason for the restriction on it is actually to encourage barnehage enrollment, despite it being more expensive for the state. Norway places a strong emphasis on the importance of barnehage for social development, and for Norwegian language development for children of immigrants and refugees. About 98% of children in Norway attend barnehage, and there is a strong social pressure to use it. Even parents here who don’t work send their kids to barnehage because it’s such an integral part of the culture and Norwegian childhood.

3 I would argue that the workers benefits we get also provide a lot of (paid) “informal care”. By law, in additional to the long paid parental leave, which accounts for a lot of informal care, every worker has the right to 20 paid vacation days, though most employers offer more (I get 25, which is common). Most parents use all of these during summer and school holidays. We also get 10 paid “sick kid” days per year, which is 20 if you’re a two parent household. We also have shorter workdays and a lot of workplace flexibility as parents of small kids. It is totally normal and expected to leave work between 3:00 and 4:00pm to pick up your kids from barnehage. All of this contributes to your point about Nordic working moms spending more time caring for their kids than Americans (this was interesting!)

3. One other thing to note on the topic of paying a fair wage to care workers is that all care workers here - formal and informal - also have universal healthcare and other rights such as vacation, sick days, paid leave, etc that in the U.S. would be considered add-on employer-sponsored “benefits” that here are paid for by the state and employee subsidies

Thanks again for this super interesting read! It’s not really my experience here that there’s more informal care than formal (would say it’s the opposite, especially compared with other parts of the world) but the data reveals some really interesting points about the value of care work, who is paying for it, and how much.